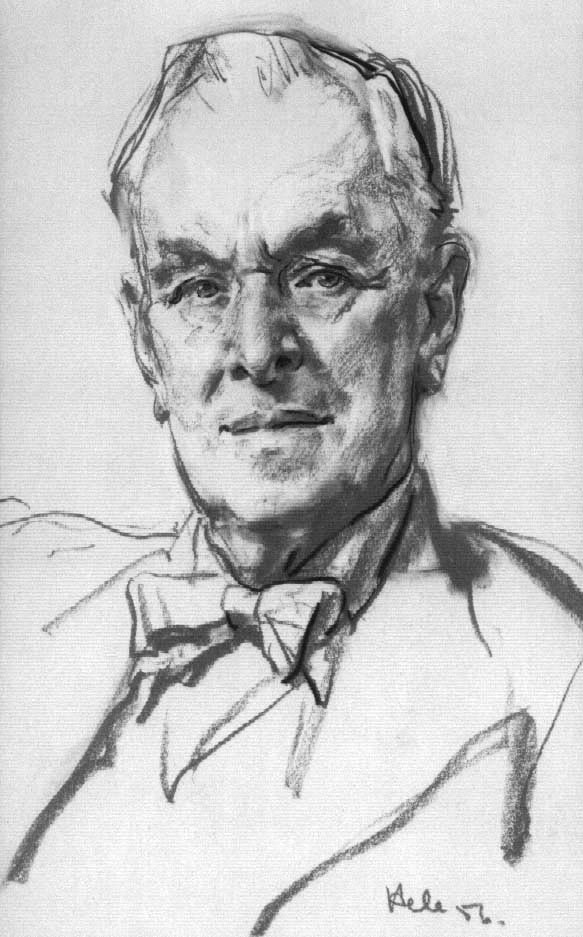

Edwin Hubert Henderson Architect

This site is dedicated to the life and work of Edwin Hubert Henderson, architect (1885-1939). Henderson was Chief Architect of the Commonwealth of Australia from 1929-1939.

A modernised classic or a disgrace to the main street – Adelaide’s Commonwealth Bank

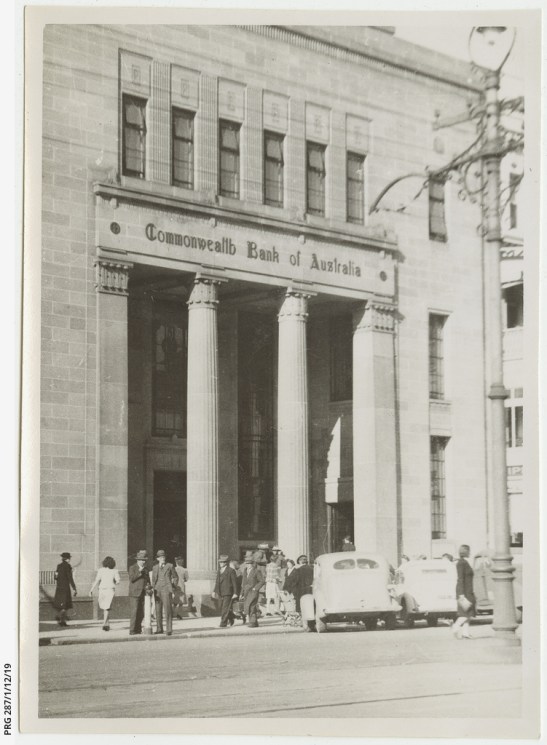

The extensive remodelling of the Commonwealth Bank’s South Australian headquarters at 96 King William Street in Adelaide in 1935 would be Henderson’s most controversial design apart from the GPO Extension in Sydney that ultimately led to this death. This episode highlights expectations of government architecture and its role in civic pride.

The original Bank – Beadles, Duels and Adelaide’s First Elevator

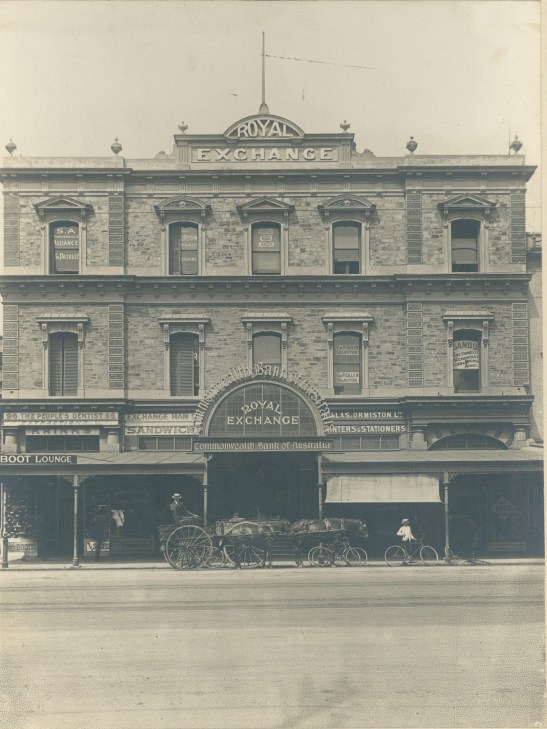

The newly formed Commonwealth Bank opened its first branch in Adeliade to little fanfare in 1912. The chosen location was the Royal Exchange building in King William Street, the main street of Adelaide on which all key financial buildings were located.

The Royal Exchange building had been a conversion of an existing warehouse to house the Adeliade Stock Exchange. Designed in 1887 by prominent local architects, Wright, Reed and Beaver, the three story building with classical ornamentation[i] was an imposing presence that was intended to capitalise on the mining boom in Broken Hill. The developed, Mr Robb, spent around £40,000 on the project, a fortune at the time.

The Royal Exchange housed the stock exchange room, a public hall, and a meeting room. A large vestibule, topped with a dome to allow in light, was surrounded with galleries opening on to the offices of individual brokers. The large veranda fronting King William Street was supported by cast iron columns and the pavement featured Mintaro slate.

The very first elevator in Adelaide was installed in the Royal Exchange “in charge of two men in chocolate brown livery, piped in cerise, while a beadle in black stood at the entrance, directing strangers”[ii]. The exchange also featured a telephone, and “speaking tubes” were connected to every room.

The brokers were prone to playing pranks on members of the public in the vestibule below, including dropping fake insects on them. In a lane between the Exchange and the Clarence Hotel, business men engaged in fencing duels with a Mr Black being the reigning champion until bested by Captain Higgins of Moonta.

The Commonwealth Bank’s branch was at the rear and accessed through an arcade of shops. Over time the business of the bank grew rapidly and it expanded to take one side of the arcade and eventually the entire lease. The bank sought to purchase the entire building and after negotiations proved fruitless, the building was compulsorily acquired in 1922[iii] with extensive alterations undertaken to accommodate the growing banking trade.

The New Bank’s Exterior Design

In 1927 the local manager Mr P W Vaughan was quoted saying there was no need for a new building as “the present structure was admirably situated and convenient for banking purposes” [iv]. Apparently his staff did not agree, and the bank had representations from its local staff for a new building for several years, with the main decision being whether to demolish the existing building or remodel. In March 1933, Bank’s local manager, L.D. Dixon ,confirmed that it would be remodelled not rebuilt – “but the remodelling would be so extensive that it would mean practically a new building”[v].

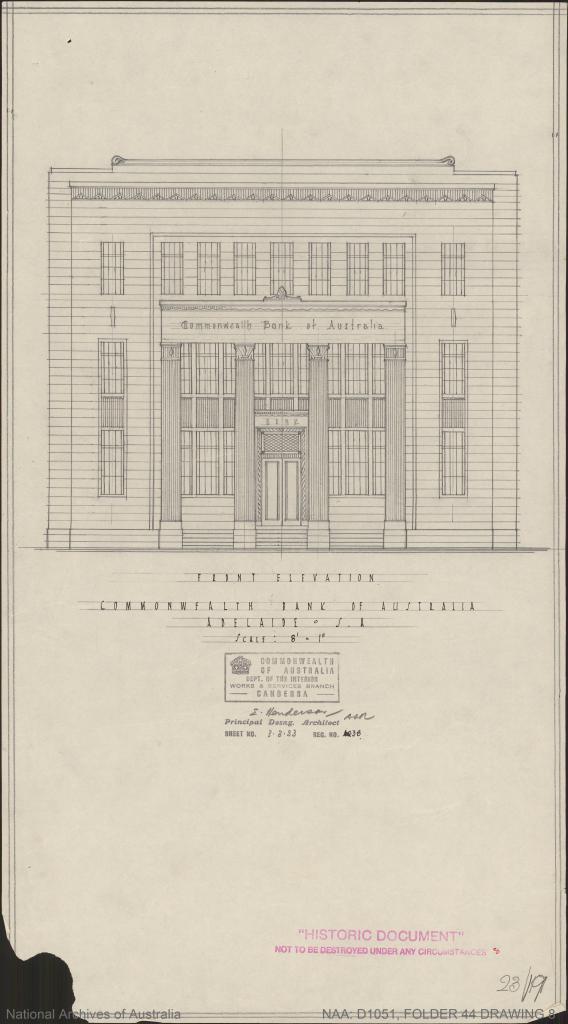

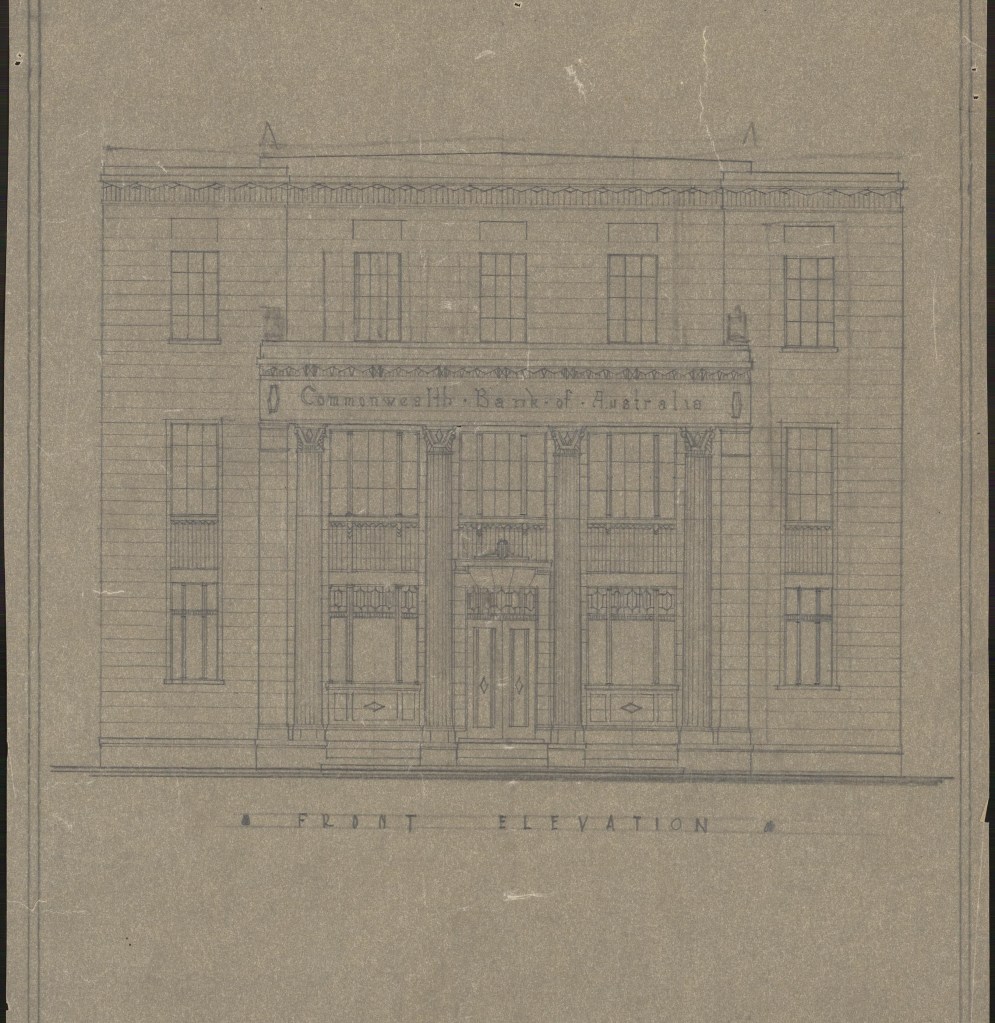

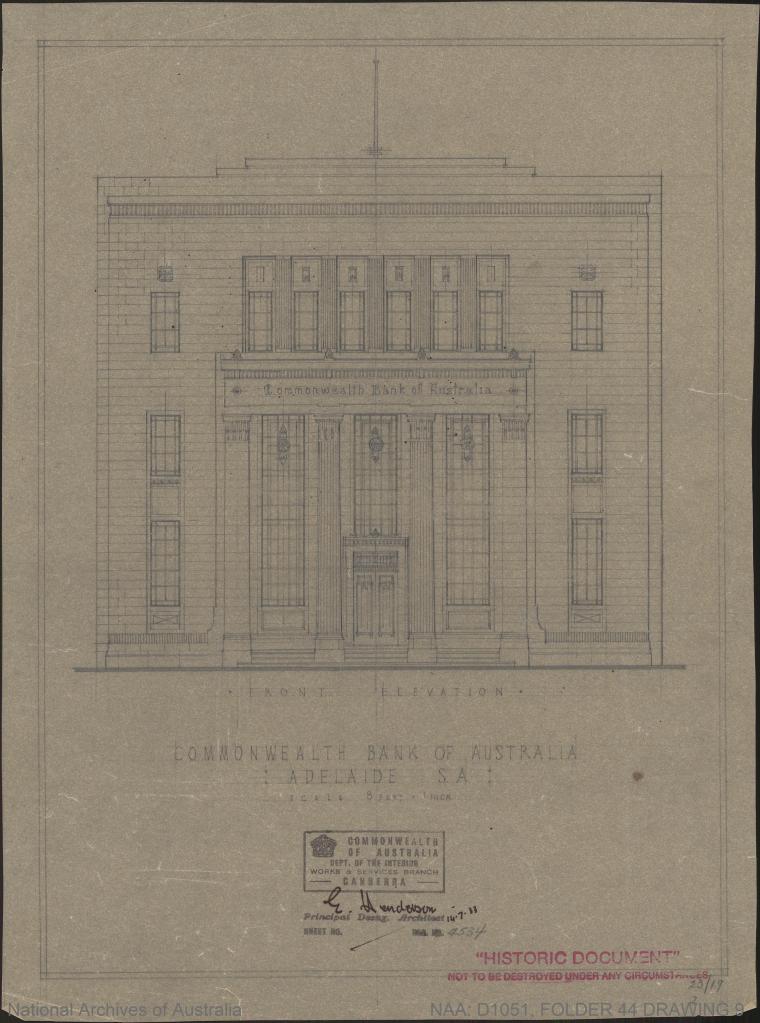

Henderson was charged with the design for this remodelling. His first design is dated 3 March 1933. The final design, of July 1933, was adopted by the Bank and was the basis of the tenders that closed on 30 October 1933, with construction completed in 1935. The cost is variously report at £50,000-65,000. Keeping the existing structure appears to have saved significant funds –for example the equivalent Perth new building erected in 1933 cost closer to £200,000. Mr W T Haslam supervised the detailed drawings and construction in Adelaide and was transferred from Sydney for the job to become in charge of the drawing room in Adeliade. The Works Director of Adeliade, R M Roland, directed the local work.

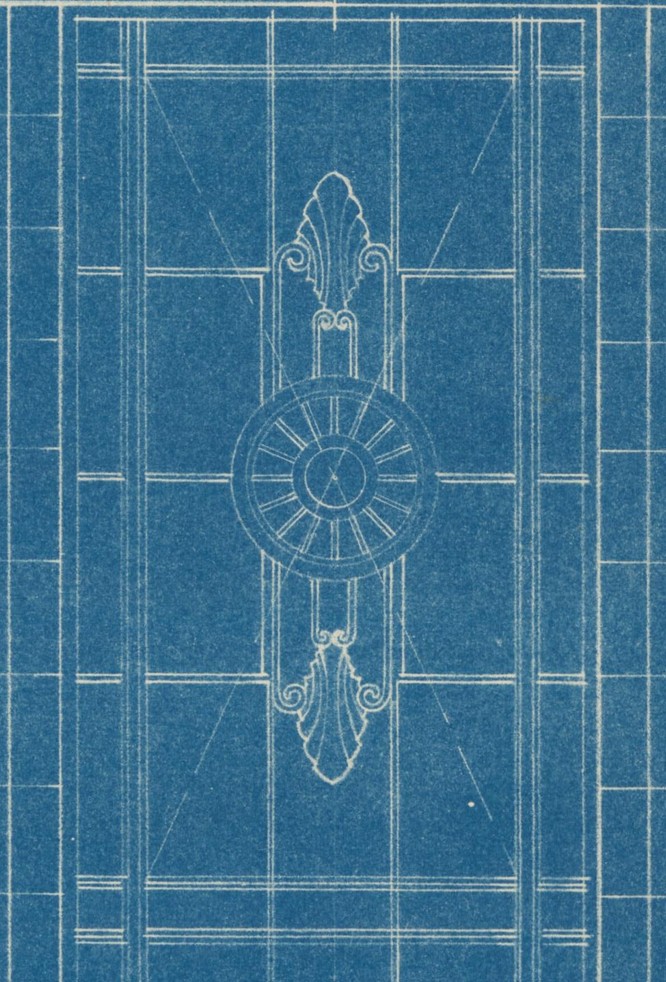

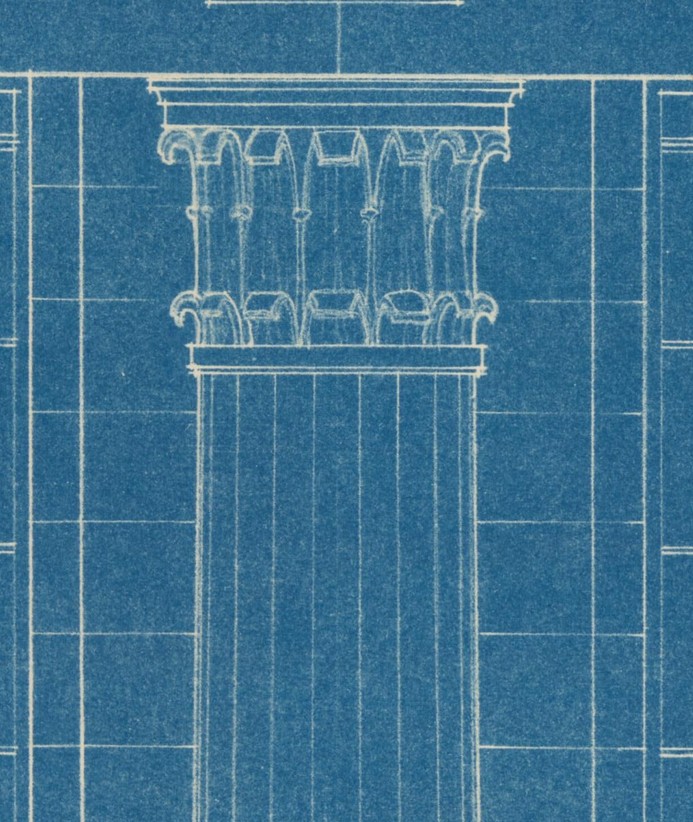

The stripped classical style of the Chief Architect’s office is seen clearly here. The symmetrical design, the recessed portico with giant order Corinthian columns spanning two stories (two load bearing, two pilasters), the emphasis on verticality, the sparing application of decoration, and the parapet to maintain the rectilinear façade. All are familiar from other contemporary Commonwealth Bank designs from the Department of the Interior. The objective always was to convey both permanence and progress.

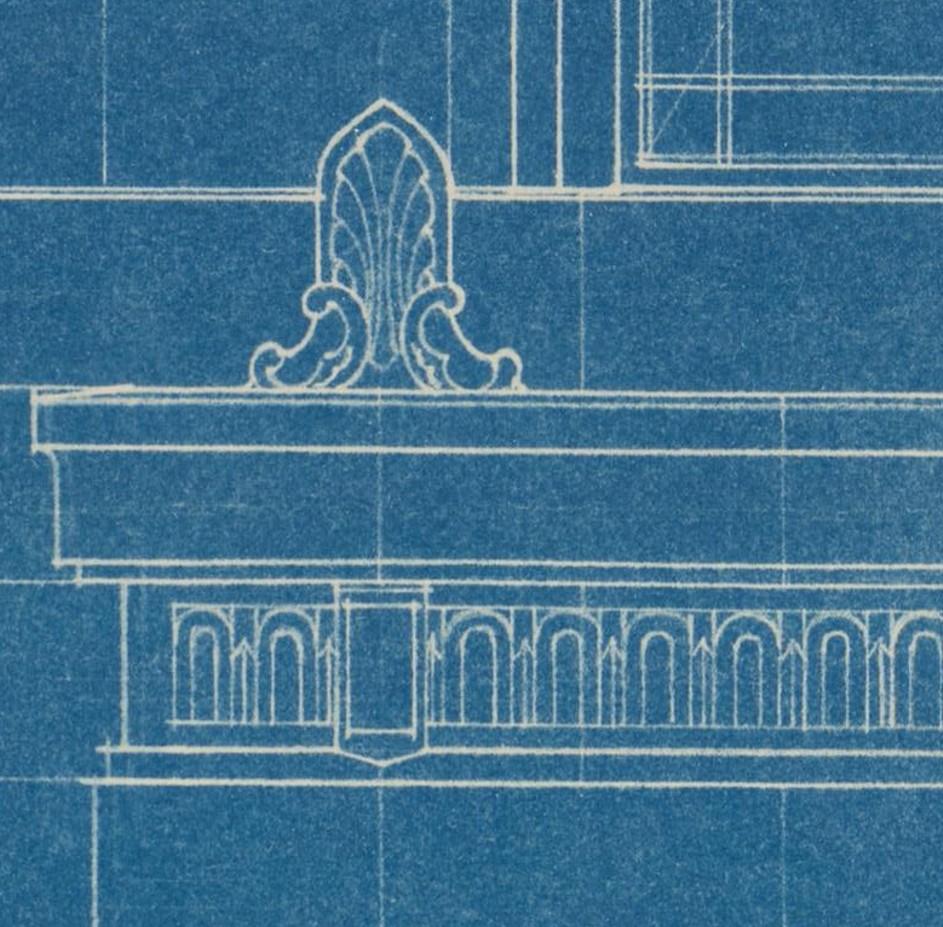

Where decoration is applied it is subtle and drawn from a classical vocabulary – above the portico, the entablature includes an upper ornament acroterion – a decorative finial featuring a stylized palmette (fan-shaped palm leaf motif) rising from acanthus scrolls. The lower frieze pattern shows repeated anthemion motifs (also called honeysuckle ornament) – a series of stylized palmette fans alternating with what appear to be lotus buds or other botanical forms, contained within rectangular panels. Above the windows on the top floor Henderson added decorative panels akin to spandrels that mixed classical motifs (paired volutes – spiral scrolls) with a geometric chevron, common in Art Deco. These patterns were also reflected in the tall windows in the portico.

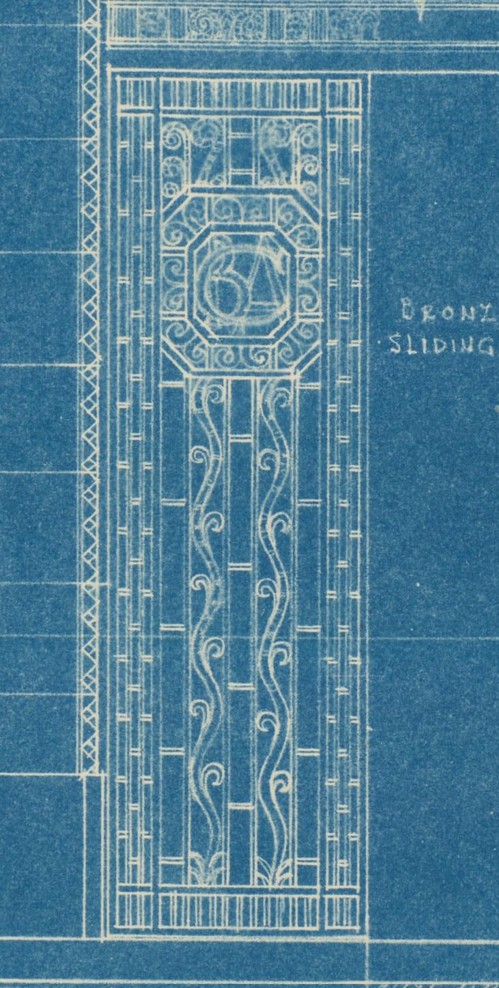

The large bronze sliding doors to the bank also reflect this mixture of classical and deco geometry, with volutes and scrolls and elegant stylized vine scrolls or wave patterns (sometimes called “running scrolls”) that flow vertically in symmetrical pairs, contained within a geometric grid framework.

Interestingly, Henderson’s final design incorporated somewhat more decoration than the first versions, which were significantly more streamlined, with less classical elements. This may well have been a result of feedback from his client, the bank, an irony given the criticism to come.

Two types of stone were used on the façade. The base of the building, the bases of the columns, the steps between the columns, and the floor of the portico were in Swanport red granite from South Australia. The balance of the facade was in Hawkesbury sandstone from New South Wales (another source of controversy – see below). Inside the portico, Henderson specified Angaston marble and NSW marble (again, having a bet each way).

Internal Design and Fittings

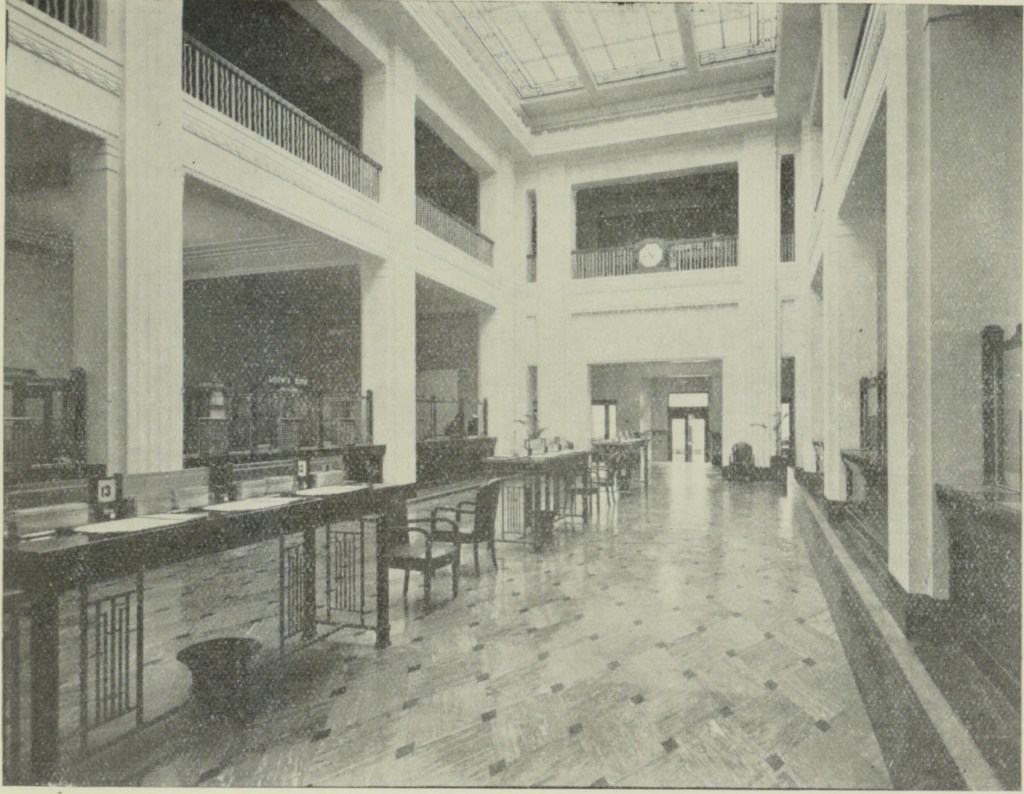

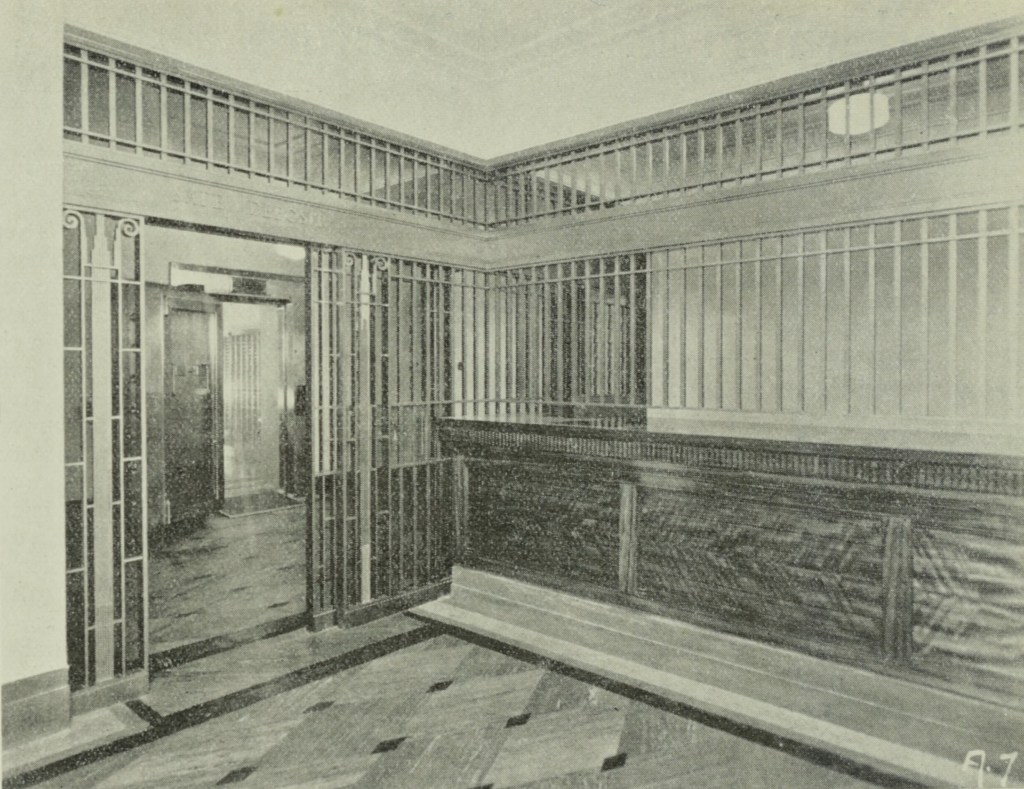

Cleverly, what the façade of the remodelling concealed was that much of existing skeleton of the Royal Exchange building (and the warehouse before it) would be retained – most of the roofs, floor joists, and floors would be retained and built around. Henderson retained the existing light well that was at the heart of the old Royal Exchange and gave it a steel structure, a mezzanine floor as well as extending the length of the vestibule which it covered to create a grand banking chamber[vi].

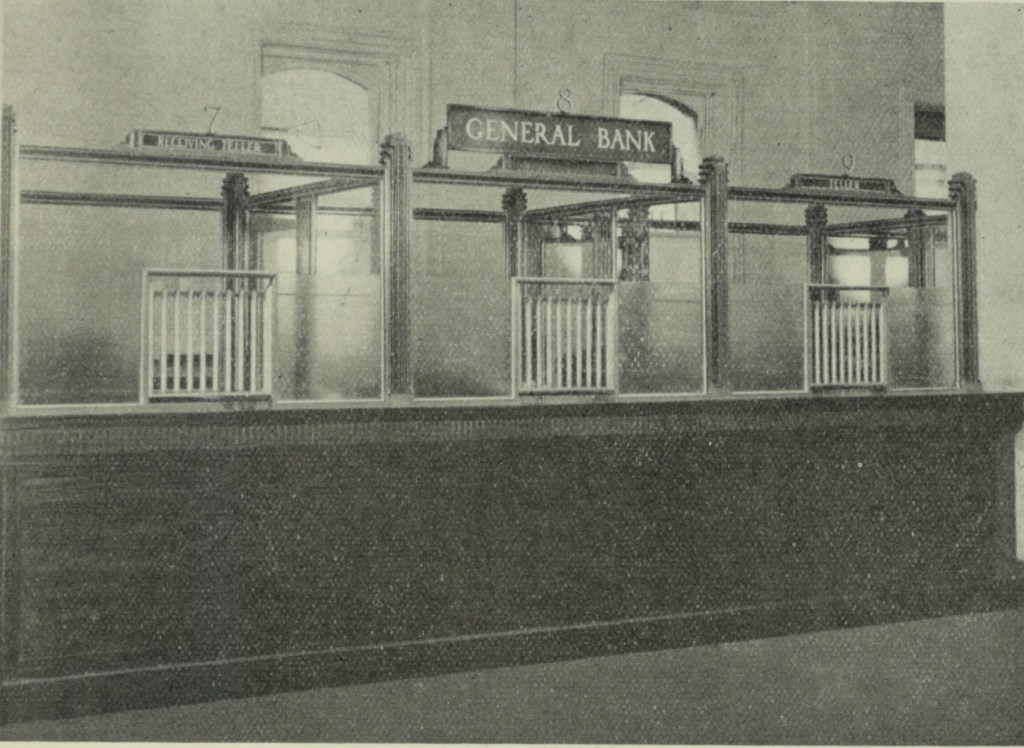

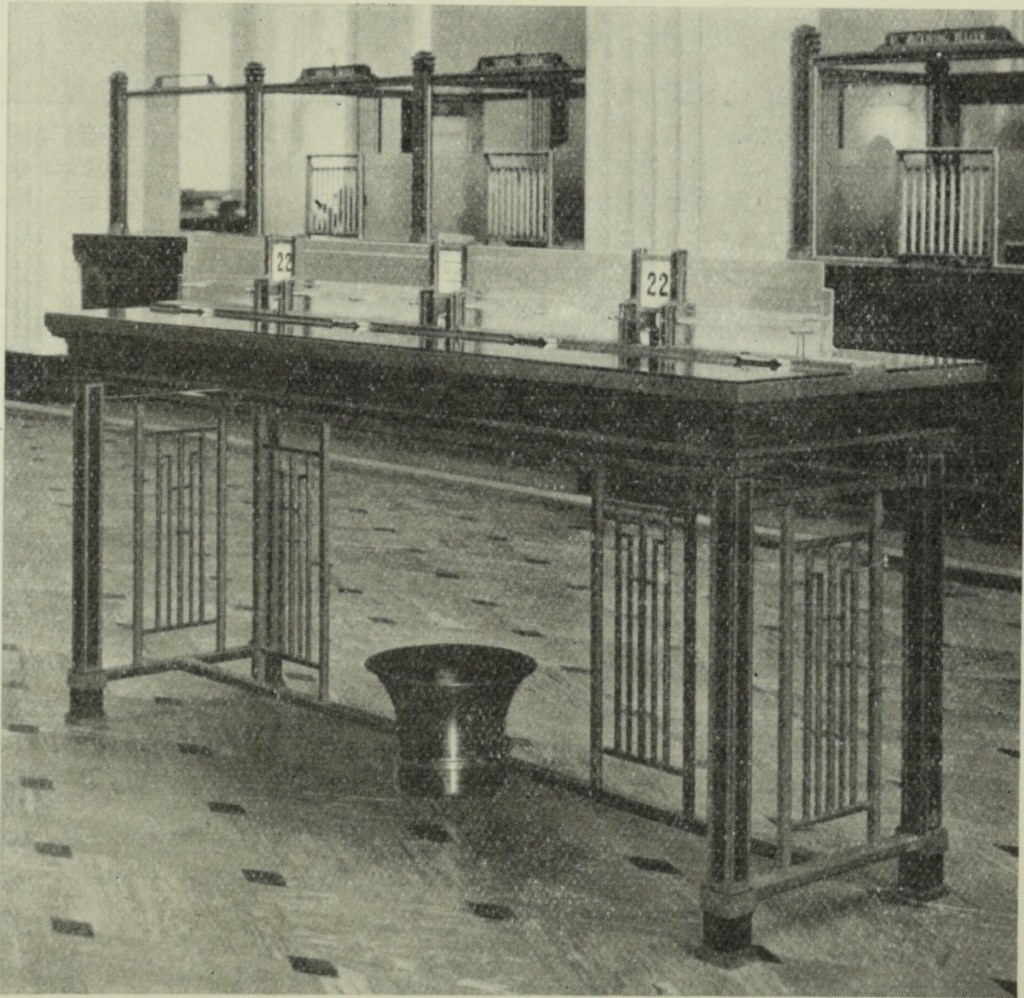

Each side of the banking chamber had counters made of Queensland walnut. Bronze screens and plate glass protected the tellers and other bank staff. As was often the case for these banks, the bronze work – of the counter screens, the directory board and the writing table and desks – was of the highest quality. These were “beautifully finished and the visibility of joint and fixing screws has been eliminated entirely”. The floor of the banking chamber consisted of diamond shaped rubber tiles in two colours (sadly we don’t know which) with a margin of terrazzo. The double height chamber gave a sense of spaciousness. At the rear was the Manager’s office (with walnut panelling), and a room for visiting officials. The accountant’s office was at the front of the chamber.

The upper floors could be accessed either by a lift or a walnut stairway. The first floor housed the note-issue, bills and securities departments, together with a spacious lounge with a library for staff opening out from it. The library was had walnut bookshelves with sliding glazed doors. Opening out from the library was a new staff dining-room, to which a kitchen was attached. The kitchen even included a dishwasher! The bank provided meals for its over 100 staff at a small cost, with any profit going to pay for books in the library (a most enlightened approach).

The second floor provided accommodation Commonwealth departments with a South Australian presence – Customs, Sub-Treasury, Bankruptcy Administration, Attorney-General’s Investigation Branch and Patents Office.

The strongroom was doubled in capacity, with a heavy eight ton stainless steel faced door was said to be “capable of defying all known methods of forced entry, including drills and oxy-acetylene blowpipe”[vii]. This strong room appears to have done the job.

The first controversy – local materials

Media commentary around the build stated that “All fittings and equipment, as far as possible, were manufactured in the State, while the labor throughout was South Australian.[viii]”. The extent of local content was, however, contested.

Murray Bridge quarries were aggrieved by the decision to use NSW stone, rather than their own freestone which they said had been used in many other buildings in Adeliade. Evidently their complaints attracted attention. Mr Butler, the Premier of South Australia, assured the Legislative Assembly that he had been in touch with the Bank and assured that the stone would be largely South Australian, “although that for the front elevation would come from New South Wales”[ix]. Alas, this was the stone that most people would see.

Debate continued. In Federal Parliament, Norman Makin, the Member for Hindmarsh, questioned the Attorney-General, John Latham about the use of New South Wales stone.

Mr Latham on this point saying that it was a poor compliment to SA to build a bank in its capital without using local stone which was of a high quality. The Attorney said it was up to the Bank and that if only local materials could be used there would be “awkward repercussions” Advertiser 5 December 1933 page 16

It is unclear what the “awkward repercussions” might be, but it appears that neither the Bank nor the Department changed the specifications regarding the stone. For Henderson this would be a familiar story, with the sandstone versus terracotta debate on the Sydney GPO Extension in 1939.

The Opening

The Bank was officially opened on Tuesday 19 March 1935 by the Chair of the Board of the Commonwealth Bank, Sir Claude Reading. He was provided with a golden key to do so. Around 270 guests from the business, political and legal worlds were invited to a reception where toasts to the Commonwealth Bank was offered by the Premier and to South Australia and Adelaide by the Chair[x]. Sir Claude was introduced by the Attorney-General prior to making his remarks. This was the first time the whole of the Bank board had met in Adelaide.

The papers commented that “No one would recognise the building in its new form as the old Royal Exchange”[xi] .

The Second Controversary – “a pigeon loft or “a rabbit hutch”

At the opening, Sir Ernest Riddle, the Governor of the Commonwealth Bank, said that the new building had been erected “in a desire to supply a structure worthy of Adelaide, where the bank’s business was steadily increasing.” Alas, whether or not this was a structure worthy of Adeliade would be a matter of debate.

In less than a week after the opening, the design of the Bank was criticised by members of the Adeliade City Council at their meeting, led by Alderman McEwin who said:

with its ‘door like the entrance to a rabbit hutch’ and its ‘top like that of a building on a small suburban street,’ the structure was a ‘disgrace to any main street’.

Ald. McEwin said that he was disappointed that so great an institution should’ be housed in such poor quarters. . He described the building as ‘mean and unobtrusive,’ and ‘lost’ between two hotels. The Commonwealth authorities responsible had without, doubt been troubled by the question of a suitable site, but the fact remained that the building was a disappointment, ‘with its poky little door between two high columns, which is like an entrance to a pigeon loft or rabbit hutch.’

The building, continued Ald. McEwin. should have been one of the most imposing in Adelaide but actually it did not bear comparison with the branch office buildings of other banks. It was a structure the like of which was expected to be seen in provincial towns and not in the third city of Australia[xii].

Ald. Homburg echoed these sentiments, saying that it was evidence of the attitude that ‘anything is good enough for Adelaide; which is being pushed more and more into the back ground.’

Debate continued, with one Councillor, Alderman Irwin, an architect himself, offering some faint praise for the design[xiii]:

as an alteration the building was a good piece of work, but the authorities had tried to alter an obsolete building in an effort to produce an important edifice and had failed dismally, for they had attempted the impossible. The choice of material was most praiseworthy, and it was not desirable to have stone the same color, so that the chancing color and texture of the type of sandstone used was advantageous. He supported the opinions of the previous speaker that South. Australia had been badly used, in that it had been given a second hand alteration instead of a new building.

Perhaps this was really the city’s own fault mused one councillor:

Cr. Bonython agreed that Adelaide had been very unfairly treated compared with other cities, but it was partly the result of South Australia’s policy of belittling itself. Adelaide had helped to pay for the fine buildings of the bank in Sydney and Melbourne, and those cities should assist Adelaide towards the possession of a decent structure. The more this city protested the more would it be to the advantage of Adelaide and South Australia.

Ald. McEwin reiterated that it is a pity the authorities did not consult the City Council.

Prominent members of the architectural profession had mixed views[xiv]. Dean Berry, himself no stronger to modern and streamlined design, defended the design:

Mr. Dean W. Berry said today that aldermen appeared not to have realised that the whole nature of the design of the bank was kept plain so that the Hawkesbury stone would show to the entrance to the bank to the bank to greatest advantage when it had “weathered.” The front of the building above the columns, looked rather plain now, but it would become much more interesting and attractive ‘when the stones had turned to different shades of brown and yellow. The columns were a beautiful piece of work, and it was unfair to compare the door to a rabbit hutch. The doorway appeared to be in proportion to the rest of the portico.

Noted Adeliade architect, Walter Bagot, a founder of Woods & Bagot, observed that “the trend of modern architectural design was towards simplicity”, and commented that “laymen should be more judicious in criticising conscientious work. The design of the bank was in accord with modern treatment of monolithic ideas”.

One of Bagot’s former partners, Herbert Jory, sided with Council’s view that Adelaide had been badly treated.

The building could have been much better, he said. Such a structure was not in keeping with the importance of a big institution like the Commonwealth Bank, and it suffered in comparison with the other bank buildings in King William street. Although the building was not a disgrace, something more elaborate could reasonably have been expected.

Building Magazine was full throated its defence of Henderson’s design praising it as a “modernised classic”:

“The style of architecture adopted is modern in its treatment; yet it does not embrace the ultra-modern forms that are characteristic of some buildings that have been erected during the past few years. Rather does it combine the accepted forms of the various periods with the modern treatment. And it gains, because of this.[xv]“

The design was defended officially, with the local Works Director responding that it really was as call for the bank.:

“Architecturally, the department has nothing to be ashamed of, but the question of policy is one for the Board of Directors of the Commonwealth Bank,”

The Federal Government was itself forced to weigh in, saying that the best possible use had been made of the site, the design was carefully considered and followed that generally used for branches of the bank. The Acting Federal Treasurer, Mr Casey, “the architects had done their best with the available site”.

Reflections

Two other major bank headquarters were built shortly after the Commonwealth Bank – the Savings Bank of South Australia (97 King William Street 1939 to 1943) and the Bank of New South Wales (Corner King William Street and North Terrace, 1939 to 1942). Both sought to strike the same balance as Henderson did, between a sense of permanence (through classical features) and progress (art deco and modernist approaches). Both were larger buildings reaching height limits, perhaps more “worthy” of Adelaide, but both adopted a similar philosophy in design, in the case of the Bank of New South Wales, being far more austere and stripped down than Henderson had delivered.

The Bank was demolished in 1981, together with the Majestic Theatre next door, to make way for a new building for the Commonwealth Bank. This was certainly a loss of a significant building but the size constraints facing the Bank probably meant that it had well and truly outgrown this original building.

[i] UniSA Architects Database James Henry Reed entry https://architectsdatabase.unisa.edu.au/arch_full.asp?Arch_ID=184

[ii] Chronicle 21 February 1935 page 47

[iii] Journal 30 October 1922 page 1

[iv] Advertiser 12 April 1927 page 13

[v] News 18 March 1933 page 1

[vi] Details for the following descriptions are largely taken from Advertiser 16 March 1935 page 22, Advertiser 6 December 1935 page 21,

[vii] Advertiser 16 March 1935 page 22

[viii] Advertiser 6 December 1935 page 21

[ix] Advertiser Thursday 23 November 1933, page 1

[x] The Recorder 19 March 1935 page 3

[xi] Chronicle 21 March 1935 page 33

[xii] Chronicle 23 March 1935 page 49

[xiii] Advertiser 26 March 1935 page 16

[xiv] News 26 March 1935 page 1

[xv] Building 12 August 1935 page 22