Edwin Hubert Henderson Architect

This site is dedicated to the life and work of Edwin Hubert Henderson, architect (1885-1939). Henderson was Chief Architect of the Commonwealth of Australia from 1929-1939.

The first National Library in Canberra

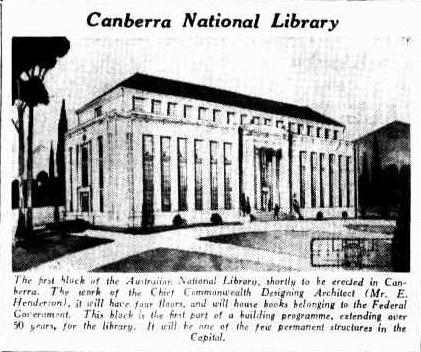

Today on the shores of Lake Burley Griffin, the National Library of Australia stands as one of the most outstanding buildings in Canberra. Clad in carrera marble, and built in the style of a Greek temple, this 1968 stripped classical masterpiece by Walter Bunning is both simple and impressive. What is less remembered is a similarly grand building originally planned for the National Library by Edwin Hubert Henderson, Chief Architect of the Commonwealth in the 1930s, a vision of which only the stage was realised.

“Worthy of the Australian nation”: The Early Years of the National Library

As soon as the Federal Parliament was established, the need for a library was recognised. In 1901 a Library Committee of Parliament was established and in its first report it stated a noble ambition:,

“the ideal of building up for the time when Parliament shall be established in the Federal capital, a great public library on the lines of the world-famed Library of Congress at Washington; such a library, indeed, as shall be worthy of the Australian nation; the home of the literature; not of a State, or of a period, but of the world, and of all time; a centre to which may gravitate as years pass, manuscripts and other documents and records of all kinds whatever, relating to the discovery, colonisation, history, and development of Australia and its adjacent regions; a shrine wherein all literary treasures may be suitably preserved, to which public funds and private benefactors may all contribute.’

Adopting the Library of Congress as a model, it seems that the Committee had in mind that the library was not just an institution, but a grand building. This ambition would take nearly seven decades to be realised.

Federal Parliament initially used the Victorian Parliamentary library while it sat in Melbourne, but during the period until its transfer to Canberra in 1927 a large stock of books and valuable manuscripts was assembled.

This included the acquisition in 1911 of the Petherick collection of Australian books, pamphlets, prints, maps, and manuscripts, consisting of up to 15,000 items. This collection was assembled by Edward Petherick (1847–1917), whose family emigrated to Australia in 1852. He became a book dealer and moved to London in the 1860s and eventually set up the Colonial Bookseller’s Agency. Petherick was fascinated by the early history of Australia and the South Pacific, and, at a time when original manuscripts were modestly priced, built up a collection of rare and unique works, including by William Dampier and Arthur Phillip. Part of the deal for the purchase of the papers was appointing Petherick himself as an archivist and granting him an annuity.

In 1912, the Commonwealth Copyright Act provided that a copy of every book and pamphlet published in Australia must be supplied to the library (as is the case with the Library of Congress). This allowed the Library to reasonably state that its collection covered nearly all printed material relating to Australia. This requirement would come to add an additional 6,000 publications per annum by the early 1930s.

The Parliamentary Library also acquired Captain Cook’s journals in 1923 at a cost of £7600. The journals were displayed in a glass case opened to the page where Cook described how he first named Botany Bay as Stingrays Harbour because of the number of stingrays in its waters, but changed this to the name we now know based on the new plant specimens collected by Joseph Banks (Sydney Morning Herald 16 May 1936). The family of Australia’s first Prime Minister Sir Edmund Barton donated papers relating to the establishment of the first Federal Cabinet. The Library also held the original copies of the Constitution of Australia.

“A Perfect Disgrace”: Pressure for a National Library Building in Canberra

This repository of Australia’s history was however housed in circumstances that did not match its significance. The Library was transferred to Canberra in 1927, with its holding increasing during the 1930s from 80,000 volumes to about 130,000. Because of space constraints, the books were stored in a range of places, including the basement of Parliament House, in the disused Acton Hotel, and in a shed at Duntroon. Donations and bequests declined, apparently because of the absence of a suitable place to store and exhibit them (Canberra Times 25 May 1933).

Successive speakers of the House of Representatives lamented this situation. Norman Makin MHR, (Speaker 1929-1932), described the situation:

“The conditions under which valuable volumes are stored in the basement of this building are a perfect disgrace. The work of erecting a suitable building to house our splendid National Library has been delayed too long…..It is not possible to house in one building the National Library and the Parliamentary Library.”

(Central Queensland Herald 4 January 1934)

These sentiments were shared by his predecessor, Sir Littleton Groom, and successor, George Mackay.

The situation worsened as the Acton Hotel was required to house the Patents Office. Possible solutions including using the West Block of Administrative Offices but this was abandoned when plans to develop a permanent administration block were indefinitely postponed. Incredibly, one idea floated was moving the books to the Lodge, which Prime Minister Scullin (1929-32) had refused to move in to whilst in office (Advertiser (26 October 1932). Usage was also increasing. Over 10 tens, the number of books taken out by Federal members increased from 91 books a week to 250. In addition, during each working week 500 documents, books and papers were issued to members (Mercury 16 October 1935). The Library was also opened up to Canberra residents to borrow from.

A consistent advocate for a permanent home for the National Library was Kenneth Binns, who became Parliamentary Librarian in 1928. A cautious, practical Scot, Binns had managed the transfer of the Library from Melbourne and did much to try and overcome the sense of isolation from other libraries experienced in Canberra.

Eventually, in 1933, the Commonwealth Parliament Library Committee considered detailed plans for the construction of a National library (Canberra Times Wednesday 24 May 1933) with funding made available in that year for construction to begin. There was support from the Opposition Leader, James Scullin, who said:

“The library which we have assisted to establish is a most valuable one, perhaps more so than the members realise, and it is obvious that the existing accommodation is not by any means adequate. I believe that it will develop into one of the most important factors in the life of the Federal capital, because I visualise the Canberra of the future as one of the great centres of culture in Australia.”

(Central Queensland Herald 4 January 1934)

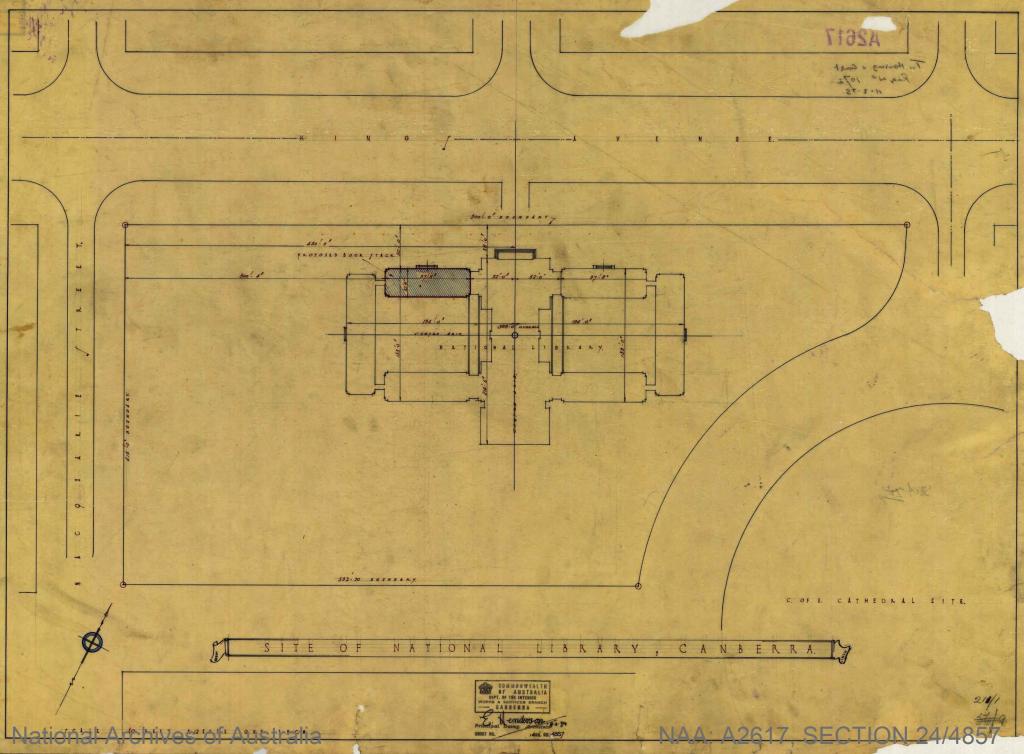

The site chosen was the corner of King’s Avenue and Macquarie Street which was occupied by part of the national rose garden, for which gifts of roses have been sent from all parts of Australia, and by the Parliamentary tennis courts and cricket pitches.

This site selection was controversial. The newspapers reported that a site recommended by officials which was in accordance with the city’s plans was rejected, and instead a site within the Parliamentary triangle chosen on the basis that ”members of Parliament would have the least possible distance to walk to procure books.” (Sydney Morning Herald 22 December 1933).

Mr. Blakeley MHR labelled the decision “gross vandalism.”

“If such an atrocity is allowed it will not only spoil the beauty of Parliament House, but will also have a similar effect upon the proposed national library building. The design of the library is a beautiful one, and is worthy of better treatment than to be jammed against Parliament House. Within half a mile of Parliament House there are 5,000 acres available for this building, but for some extraordinary reason the Government is determined to have the library against Parliament House.”

(Argus 26 December 1933)

The decision stood.

“A great national repository”: Henderson’s Plan for the National Library

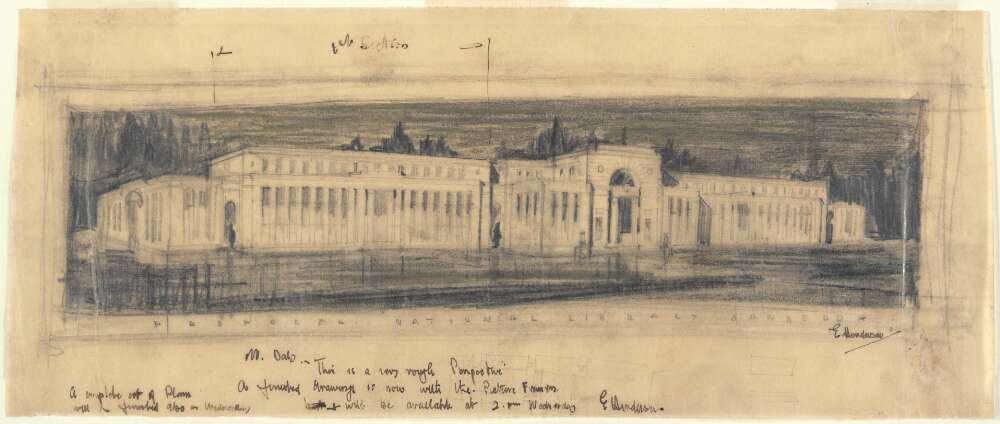

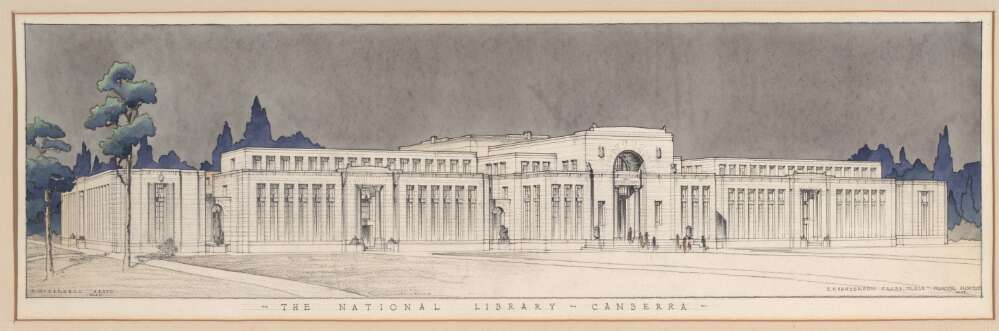

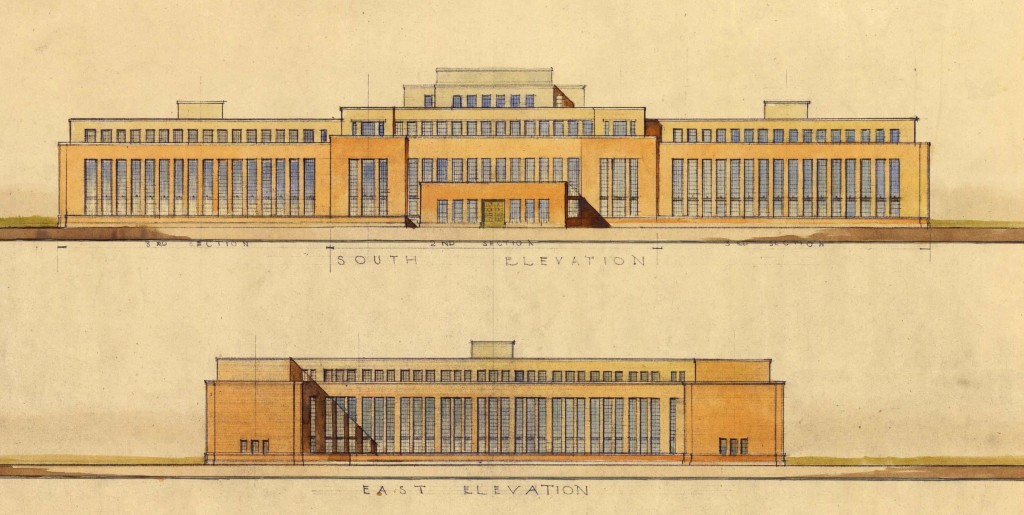

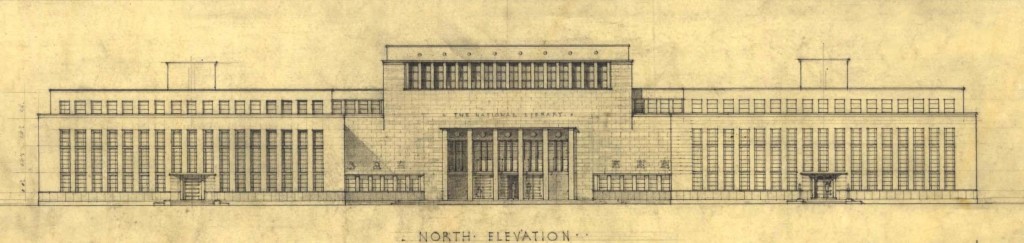

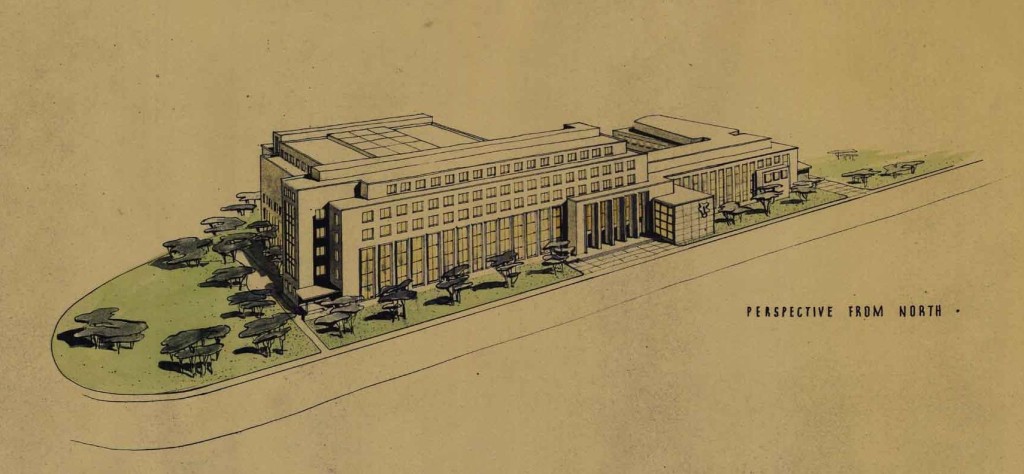

Consulting closely with Binns, Henderson developed a plan for a National Library that could be developed in stages. In initial sketches, then later detailed renderings, Henderson fleshed out what would, if built, be perhaps his greatest legacy.

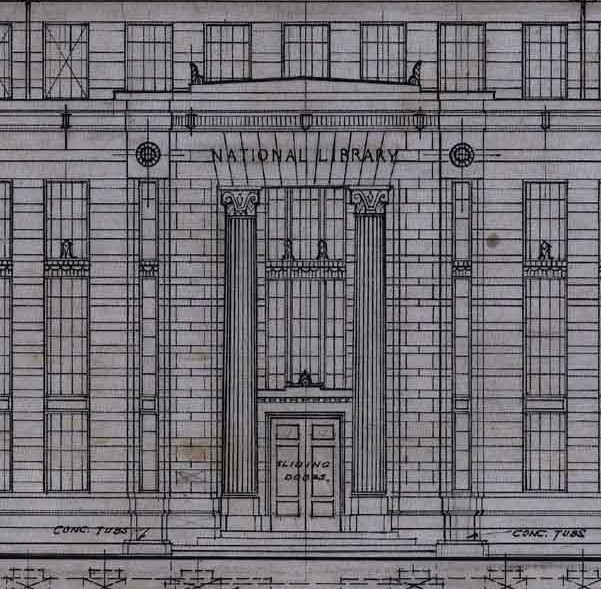

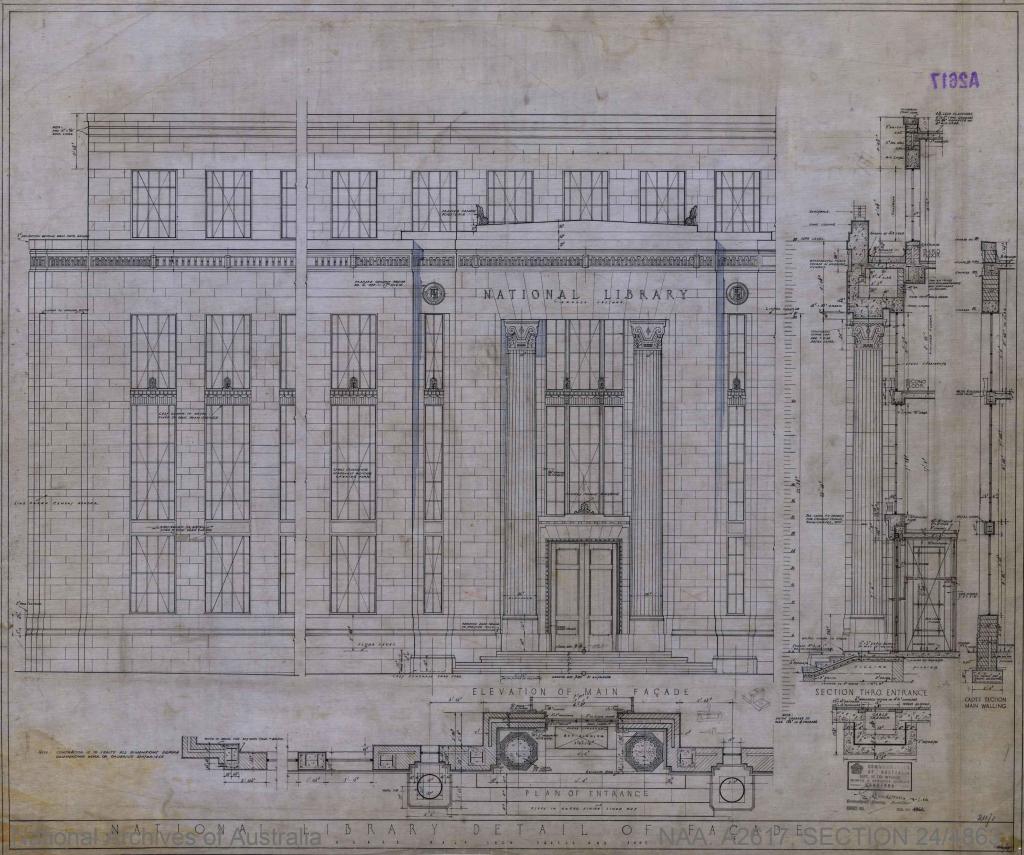

In his usual stripped classical style, Henderson envisaged a library complex surrounding two courtyards. Four book stacks would stand at the front and rear, flanking a central core comprising the main entrance, a dome, a lecture hall, reading rooms, and accommodation for staff. One side wing would house an art gallery and museum whilst the other cater for administration . The complex would be set in nature with extensive gardens. The library will be 300 feet long, and would be four stories in height.

The total cost would be £100,00 with a horizon of five years between the first and later stages as more space was required.

The buildings in the plan had a strong vertical presence with narrow long windows. The front entrance featured a curved arch over the entrance, with two corinthian columns framing the doors. The massing of the overall design is pleasing, steeping down slightly from the main entrance, to the stacks, and to the side buildings. The building would be in stark white in keeping with Parliament House. In some ways this building would be more ornate than the Parliament Building and certainly more imposing – Murdoch’s design for Parliament was a three story building of which only two stories were obvious.

The overall design was made public and was warmly received.

The Government architect, Mr. Henderson (who by the way, has been responsible for most of the Commonwealth Bank buildings throughout Australia) has completed an imposing design for the library

(Central Queensland Herald 4 January 1934)

The Sydney Morning Herald called it “a magnificent edifice” (6 May 1936) that would “complete the square of public buildings in the heart of Canberra—all masterpieces of symmetry, facing a park of lovely trees and rose gardens within rose gardens.” (26 October 1935). It would be:

“a great national repository which will eventually accommodate Australia’s best literature and historical relies, it is certain to have a strong influence on the cultural development of Canberra.

(Newcastle Morning Herald and Miners’ Advocate 21 October 1935)

Regrettably, this design would never be realised.

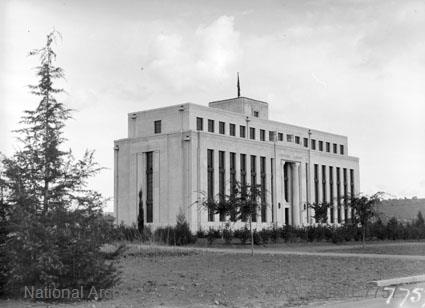

“An exquisite, harmonious building”: Stage One is Built

The British Poet Laureate, John Masefield, laid the foundation stone of the first stage in 1934. Masefield donated an early edition of Dampier’s voyages as a gift to the Library (Sydney Morning Herald 16 May 1936)

Over a two month period in mid 1935, books were transferred to the new building. The task was significant, with the books being kept in the exact same order so they can be placed on the new shelving in exactly the same Dewey system designation (Canberra Times 29 June 1935) . A call went out to local borrowers to return their checked out book or face a three pence a week fine. The Librarian proudly advised that the dutiful citizens had returned each and every book (Sydney Morning Herald 16 October 1935).

The first stage of the National Library was opened on 18 October 1935. It cost £14,800 and measured 90ft by 40ft. The building, which contains 70,000 books, and had provision for 100,000, (Mercury 16 October 1935). The Parliamentary Library was maintained at 50,000 books.

The Sydney Morning Herald (26 October 1935) provided a detailed description of Henderson’s building:

The first book-stack of the National Library now stands in its place, exquisitely symmetrical and dignifiedly tall. Its surface is of Hawkesbury River sandstone, crushed and mixed with cement, and is a soft grey colour. It has long, narrow windows of actinic glass, a lovely shade of moss green from the outside, but giving an almost moonlight effect inside. The light is most soothing to the eyes—white, but as though coming through water, and the glass is 71 per cent, heat-absorbent. Thus the bookbindings will not fade, and the library will have a comfortable temperature on summer days. This is the first time this new glass, made by an Australian firm, has been used.

The entrance is up a flight of four wide steps between two tall pillars, with straight portico above. On one side is the stone laid by the Governor-General, Sir Isaac Isaacs, and on the other the stone laid by the Poet Laureate, John Masefield, when he was in Canberra last year.

Within, the doors are of mountain ash of soft brown, shaded like velvet, and each side of them are two stoneworks let into the wall. They are the shields of England, Ireland, Scotland, and Wales, taken from the House of Commons, Westminster. When the Commonwealth Librarian, Mr. Binns, was in England recently, demolishing and repairs were being made at Westminster, and he secured these. They are about 18 inches square in size, and look well in our Canberra Library wall. They give an interesting touch, with London smoke still mellowing the old stone. On an end wall is a fine bronze of Hans Christian Andersen, presented by Mr. Heyman, a Danish maker of medallions, in honour of the centenary of the publication of Andersen’s first book—which is this year.

The ground floor, at the present, is divided into a reading-room and book shelves. When the library is completed the reading-room will revert to space for books, but, in the meantime, the general public may sit there in the greatest comfort, for there are Windsor chairs at all the tables; and the backs and arms of Windsor chairs seem to have lived throughout the ages by virtue of their ease to the human form. Our librarian is responsible for these. He saw them used in the library at Philadelphia, and was struck with the good sense. There are 12,000 popular books here, novels, histories, biographies, and travel books, carefully chosen from the main library.

On the first floor are the electoral rolls of the whole of the Commonwealth. They are bound in deep red leather, and take up very nearly all the space there, giving a very rich and solemn air to this part of the library. The next floor has scientific works, and lots of rare old books stand in the shelves here.

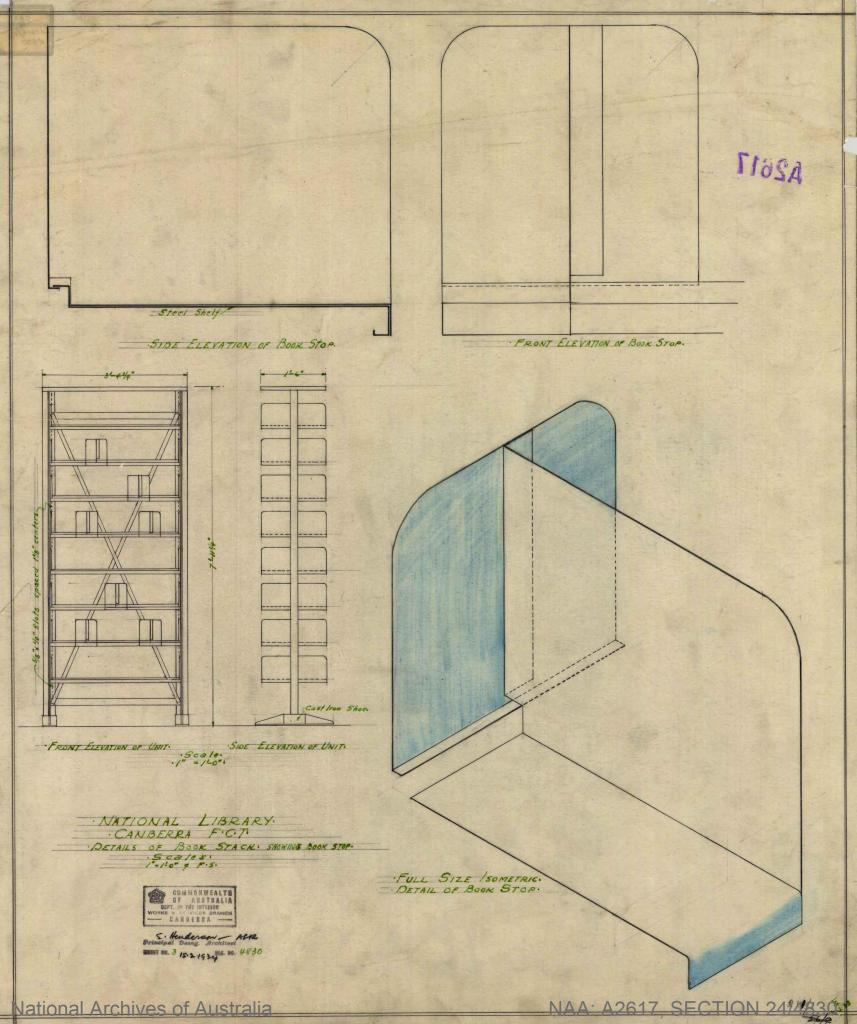

On the top floor are all Australian books, and it is a revelation to see the great amount our Australian publishers have put out. Also here, in specially made wide, shallow drawers are maps and atlases. All the shelves are of steel, coloured French grey, and the walls are of parchment yellow. Automatic fire alarms are neatly fitted into the white ceilings, and frosted globes cover lights hanging in graceful lines.

In a basement are all the workings for pumping artificial air through the whole building, so that windows need not be opened, and no dust comes in to damage the books.

There was in addition a section containing full reference works and records of the history of Canberra, dating back to the earliest days (Canberra Times 12 March 1938)

As usual, Henderson paid close attention to every aspect of the design of the building, including designs for the book shelves and the reading desks. Not only would the building be beautiful it would also be functional.

“The fragment of a plan” Further Developments

There was criticism of the scale of the proposed plan. Even Kenneth Binns, the foremost advocate for the project, was forced to defend it publicly following criticism of the proposed spending. In a letter to the Editor of the Melbourne Herald (2 July 1935), he wrote:

Sir,— Your reference to “the erection at Canberra’ of immense institutions — the latest being a palatial library at a cost of hundreds of thousands of pounds.” preceded as it was by the reproduction of the architect’s complete plan for the National Library building, must certainly lead your renders to believe that the whole of this building is being now erected for our library.

The position, however, is that it is only one very small section of this plan which the Commonwealth Government has erected at a cost— not of “hundreds of thousands,” but of only £13,000— and that it is the intention of the Commonwealth Government only to proceed with further additions to this small beginning as the development of the National Library makes this necessary. The erection of the whole building as shown in your reproduction will therefore be a matter of many years to come.

As indicating that this will not be the “lavish” structure suggested. I may mention that, unlike Public Library buildings in the State capitals, it is being erected with only an imitation stone finish and without expensive external or internal decoration, whereas the Public Library of New South Wales at the present time is engaged upon the erection of a section of its new Public Library at a cost of over £80,000 —but, knowing as I do the totally inadequate provision for libraries throughout the whole of Australia. I would be the last to complain of any legitimate expenditure for library development The section at present being erected is required to meet an urgent need, for the National Library— which meets the requirements of Government Departments, the public of Canberra, and the Canberra University College, as well as making available on loan to research students anywhere in Australia material which they cannot secure elsewhere— has had to utilise a wing of one of the hotels in Canberra and also a galvanised iron store at Duntroon for the accommodation of the 70,000 volumes which will be immediately moved into the new building.

When I mention that the total expenditure by the Commonwealth lost year on the Commonwealth Parliamentary and National Library was only £7577, it can hardly be claimed, in view of the wide range of services which it Is required to give, that it is an expensive luxury. Indeed, when it is remembered that the Dominion of Canada— which our national pride makes us regard as comparable in importance with Australia— expends on its purely Parliamentary Library more than three times this amount, and on its Archives Department more than four times as much, the Commonwealth Government can hardly be accused of extravagance in providing for its own needs.

Binns must have chafed that the State Library of New South Wales was being extended at a cost of £80,000 at the same time to create the magnificent portico to the Mitchell Library. Of even greater chagrin would be the fact that the NSW Library was often called the “National Library”.

Henderson’s Library stood somewhat alone on its site near Parliament. American scholar C Hartley Graham observed that “it is a trifle odd to come upon the first wing of the National Library standing with soldierly rigidity in the midst of a vast paddock”. In a history of the Library Peter Cochrane described the Library thus:

The new building, small, unfinished, “reminiscent of a matchbox standing on its side’, a fragment of a plan that would never be realised.

Cochrane 2001:30

But planning continued for the realisation of the rest of Henderson’s plan. In August 1939, just two months after Henderson’s death, his deputy Cuthbert Whitely was still developing plans for the central buildings of the complex. Planning was still taking place in 1941, even as the war came to Australia. However at this point, the design was changing, taking on a far more international style. The Corinthian columns were gone but the book stacks would still be integrated. In some ways this design is more similar to the style that Henderson brought to the Sydney GPO Extension. It may be that the ornamentation of the 1934 design was a response to the desires of the client, which may have changed in later years.

After the War, the Government announced that when the Library was built, it would contain a wing dedicated to President Roosevelt. The design changed significantly.

By 1952, the existing building was condemned by a visiting American academic as “inadequate” and “of no particular architectural distinction” . “By American standards, it was economic, efficient and modest – if anything too modest”. (Canberra Times, 3 July 1952). Binns’ successor as Librarian complained to the Public Works Committee that the building was “dingy” and “half finished” (Biskup 1983: 33).

The pity is that this was a verdict on a design uncompleted. The Librarian of the Commonwealth forecast a crisis very much along the lines of the situation in the early 1930s – too many books, stored across multiple locations, with a poor user experience.

The 1957 Paton Committee found the conditions of the Library accommodation inadequate and recommended a National Library as a stand alone statutory body (an idea floated in 1935). This was adopted in 1960. In 1963, Prime Minister Menzies announced that working plans were being completed for a “very fine” National Library building (Canberra Times 12 March 1963). Apparently Menzies asked for “something with columns” in terms of design.

In 1968 the National Library building opened in Canberra. Designed by Walter Bunning, it was built in the style of a Greek temple – with columns as requested. Cost savings meant that the number of columns, instead of matching the number on the Parthenon, were two less. The materials were of the highest standard and the cost to match – $7 million. Unlike in Henderson’s time, attitudes to spending on public architecture in Canberra had changed.

Henderson’s original National Library Building became the Canberra Public Library Service Headquarters and was demolished to make way for the Edmund Barton Building designed by Harry Seidler, constructed between 1969 and 1974.

Had Henderson’s full design been built, it would have been a magnificent addition to the architecture of Canberra, complementing old Parliament House. For Henderson it would have been a career highlight. Unfortunately it ranks with the Brisbane GPO as his greatest unrealised work.

References

Biskup, P. 1983. Library models and library myths : the early years of the National Library of Australia. Sydney. History Project Inc.

Burmester, C.A., Petherick, Edward Augustus (1847–1917), Australian Dictionary of Biography online

Cochrane, P. Ed. 2001. Remarkable Occurrences: the National Library of Australia’s first 100 years 1901-2001. Canberra. National Library of Australia.

National Library: https://www.nla.gov.au/about-us/our-building/history